15 - Hiru ahoko ezpata

Leo

usoa / Bi behatz /

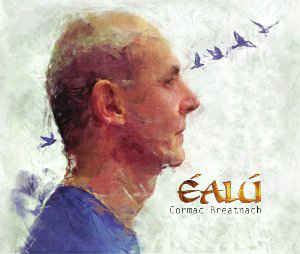

Cormac Breatnach-en ezpatadantza

('The Three-Bladed Sword') - 4´29

'Leo the Dove' / 'The Two Fingers' /

'Cormac Breatnach's Sword-Dance'

(Music: Alan Griffin)

(Arranged

& produced by Joxan Goikoetxea

& Alan Griffin)

Recording

engineer: Joxan Goikoetxea

Recorded at Aztarna Studio (Hernani, Gipuzkoa) throughout 2017.

Mixing

and Digital Mastering:

Mikel F.Krutzaga – Musikart Studio (Amezketa - Gipuzkoa).

Alan

Griffin:

low whistle, whistle, Jew's harp, alboka

Joxan Goikoetxea: accordion,

keyboards, percussion, sound FX

Fiachra Mac Gabhann: bouzuki,

mandolin

Juanjo

Otxandorena : bouzouki

Peter Maund: târ,

riqq

Juan Arriola: fiddle

Some

ceremonial dances from the Western Basque Country have a characteristic

time-signature of alternate bars of 6/8 and 3/4. There appears to be

no generic name for these tunes and for convenience most musicians refer

to them as 'ezpatadantzak', 'sword-dances', which some are and others

are not. The tunes here follow the traditional rhythmic pattern.

The first and second tunes are not alboka-friendly, but the third is

Nº 78 in Halfway to Hell: Albokarako 333 doinu.

All Alboka albums must have at least one set of sword-dances. After using up all the traditional tunes we began to compose our own and here are three more. I asked Joxan what he thought of the tunes. 'Rather than sword-dances they're labyrinths in sword-dance form', he said.aid.

The third tune was named in hopes that Cormac Breatnach

might be flattered into playing it.

As for the other two titles, I'd be happy to tell you about them in

conversation but would rather not set anything down in print.

Ezpata-dantza

(Sword-dance)

Ezpata-dantza' is a generic term that

may in principle by applied to any dance performed with swords. In fact,

the Basque tradition has several

different dances with the same name,

e.g. in Xemein, Zumarraga, Deba,

Legazpia and Lesaka, although

nowadays in the latter at least

sticks are used rather than swords.

Moreover, there exists a standardised

Gipuzkoan sword-dance and indeed

a new one has been created

in Pamplona. Nonetheless, the term,

especially in the first half of

the twentieth century,

became synonymous

with the 'Dantzari Dantza' of

the Duranguesado region.

The

reason for this curious fact

lies in the special interest taken in

this dance by the PNV

(Basque Nationalist Party)

and by their leader Sabino Arana

in particular. Arana's enthusiasm

dated from 1886, when he first

saw it danced in Durango.

Like almost all Basque nationalist

symbols, it had in its favour

its Biscayan origin, and in this

particular case Arana emphasised its majestically virile character,

which was otherwise lacking in dances

like the ribbon-dance (Arana Goiri 1987).

During his imprisonment Arana composed

words to go with the entry

march for this dance, which later

became the 'Euzko-Abendearen Ereserkia',

or Basque national anthem,

and which is the current anthem

of the Basque Autonomous Community

(Jemein & Lanbarri 1977:288).

Thanks to the Basque Nationalist

Party (Arana Goiri ibid.), a dance that

at the end of the nineteenth century

was performed in scarcely four localities

of the Duranguesado spread throughout

the entire Basque Country and was

used at most of the Party's functions.

In 1910, dancing-lessons commenced

in the Batzoki (PNV party centre)

in Bilbao (Camino y de Guezala 1991:65);

in 1932 the Bizkaiko Ezpatadantzari

Batza (Biscayan Association of

Sword-Dancers) was formed,

to be followed shortly by similar

organisations in other territories.

In 1933, on St Ignatius' Day,

275 Biscayan groups came together

to dance in San Mamés football

stadium in Bilbao.

During the same period the Gipuzkoan

branch of this association had

1,200 members and there were 600

in Alava and 500 in Navarre (Tápiz 2001:105). We may infer from

the term 'ezpatadantzari'

in the names of these associations

that the designation 'dantzari-dantza'

was probably unknown beyond the Duranguesado region.

As often occurs in these cases,

therefore, a specific term, in this case 'ezpatadantza', can lack a

precise meaning

or even a clear logic in many senses.

As far as the music is concerned,

for example,

it would not have been unusual

for one or two of the melodies to have

taken on this name. For these are

melodies that in one form or another

reappear in all the 'ezpata-dantzak',

though in very interesting variations,

as often happens in these cases.

However,

in music the term 'ezpatadantza'

is more often used to denote a genre

defined by a particular rhythm; specifically,

the unusual rhythm of certain parts

of the 'Dantzari-Dantza'.

The first to note down this dance

was Wilhelm von Humboldt, after

a visit to the Basque Country in 1801.

Under the title of 'Children's dance

from this Duranguesado region' he

wrote four melodies in broken

6/8 & 2/4 rhythm.

At

the beginning of the twentieth

century Azkue collected the majority

of the parts of the Berriz dance of 'ezpatadantzaris', in the process

drawing attention to the pipe-and-tabor

player (tamborilero) Hipólito Amezua.

To sum up, this rhythm, like the 'zortziko',

is considered to be one of the most characteristic of Basque music.

Source: Enciclopedia

vasca Auñamendi

Author: Carlos Sánchez Ekiza

Eusko Ikaskuntza

One of the most important things to be decided at the outset when recording

a track is the tempo.

The Good Producer’s Guide recommends first trying it

out at different times of day, given that our biorhythms vary with the

hour: readings taken first thing in the morning will be different to

those after a heavy lunch or at the witching hour of night..

I’m not going to reveal our secrets for

choosing tempos any more than a good chef will explain his recipes,

but I would like to point out that after the first ezpatadantza recording

on an Alboka album (‘Launako’, 1994) the speeds of the sword-dances

shot up dramatically in successive recordings, 'Iparhaizea' (1998),

‘Dantzau daigun/Binako’ (2000) and ‘Ekihaizea’

(2004), before returning to approximately the same speed as 1994 on

the present recording of 'Hiru ahoko ezpata'.

Is there any musical expert or even psychologist

out there who might make a short study and draw conclusions?

The duet by Fiachra and Juanjo on mandolin and

bouzouki is a true delight. Sadly, it’s a delight that we’ll

never hear again.

I’d like to thank Juanjo

(Pepe to his friends) here for his sterling bouzouki work. His development

on the instrument over the last 17 years is reflected in the many projects

he’s been involved in so successfully.

The harmonic and rhythmic lines on these sword-dances are typical of

his style and in many ways point the way for the rest of the instruments.

Eskerrik asko Juanjo!

As

for Cormac Breatnach, to whom Alan dedicates the last tune on this track,

we greatly enjoy his visits to the Basque Country, his mother's homeland.

And

we remember with pleasure his help in getting to play at the William

Kennedy Piping Festival in Armagh in 2009, where he joined us onstage.

Cormac

is one of the international artists who play Basque tunes in their concerts,

in Cormac’s case in his own inimitable way.

Eskerrik asko Cormac!